Scents are invisible, intangible, volatile, and transient. Our olfactory register is bombarded as we navigate daily life. Nearly all the products we use on our bodies (shampoo, lotion, make-up, toothpaste) and our homes (laundry detergent, dish soap, floor cleaner) are scented. We seek to control the aromas we find undesirable; we use antiperspirant to suppress natural bodily odours, deodorisers to mask unpleasant smells. Even just catching the whiff of sugar is enough for the brain to produce dopamine, demonstrating the capacity of this sensory register to affect the body. To smell an object is a highly intimate act; the scent enters the nose and settles on the olfactory receptors inside the body. When encountering an unpleasant odour we recoil and pinch our nostrils effectively blocking the scent from entering. When something smells pleasant, such as freshly baked bread or the perfume of a flower, we lean in trying to capture and inhale as much of it as possible.

Scent receptors are located in the olfactory cortex, a zone of the brain that overlaps with the limbic system. This part of the brain facilitates behaviour, emotion and long-term memories. As a result of this overlap, scents are often linked to memories and form associations that are highly individualised and subjective. The capacity for odours to involuntarily call up rich autobiographical memories is known as the Proust Phenomenon; named after the French writer Marcel Proust and his evocative description of the recollections induced by the scent of tea-soaked biscuits. These scent-induced memories are both incidental and unmediated, triggered only when the scent is re-encountered.

In classical philosophy, vision is linked to the mind and intellectual pursuits and as such, is valued over the other modalities. In contrast, taste, touch, and smell are commonly recognised as bodily senses, in that to be understood or ‘known’, they are experienced with the body. As the avant-gardes of the 20th century began to break down the hierarchies of traditional subject matter, mediums, and fine art definitions, they also began to question the privileging of sight over the other senses as the primary way to engage artwork. More recently, contemporary practices demonstrate repeated effort to access an unmediated reality or direct sensory experience, culminating in work that seeks to directly activate the viewer through bodily sensation.

Right: Bill Noonan, can’t see the forest for the trees (2018), ceramic, wood veneer on canvas, shoes, LED candle

reminiSCENT surveys contemporary artists initiating multisensory experiences through olfactory encounters. The artwork in this exhibition engages a number of dialectics including foul/fragrant, pleasure/displeasure, natural/synthetic. Claire Anna Watson and Bill Noonan’s sculptural-installations demonstrate this opposition. Whereas Watson sought to capture the essence of the natural realm by working with a perfumer to distil the forest into a single scent, Noonan accentuates the synthetic fragrance of commercial deodorisers by including ubiquitous pine air-fresheners.

Right: Susanna Strati, Reliquary – Orb of Love and loss (2017), Oxidised bronze infused stainless steel, red sintered nylon, gold plated sterling silver, magnets, olive oil, rose oil, frankincense infused balm, beeswax, 9.05 x 7.6 x 6.6 cm

Bodily scents are odours we try to suppress with deodorants and enhance with perfumes, a challenge Melinda Young and Susanna Strati have achieved through the fashioning of jewellery that scents the body. Young’s neckpieces are activated by bodily heat to release aromas of nutmeg, frankincense, or Pears soap. Strati’s ring, Reliquary – Orb of Love and loss (2017), recalls the shape of a Catholic thurible used to distribute incense during worship. Like the swinging of the thurible, the scent of frankincense, rose oil, and beeswax is dispersed by the movement of the hand wearing the ring.

Right: David Capra, Eau de Wet Dogge (2015-2016), glass, perfume, label 12 x 12 cm

In contrast to the artworks that perfume the body, Martynka Wawrzyniak’s Eau de M (2014) coerces the audience into an intimate encounter. In what she describes as a “guerrilla gesture”, Wawrzyniak took out a fragrance advertisement in the May 2014 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. The perfume strip contained her sweat essence and an unsuspecting public sniffed her body odour without hesitation. In speaking of such interactions, Georg Simmel writes “smelling a person’s body odour is the most intimate perception of them; they penetrate, so to speak, in a gaseous form into our most sensory inner being…” (1). David Capra’s Eau de Wet Dogge (2015-16) presents the scent of his dachshund Teena during bathtime. In this instance, Capra captures the erasure of body odour (his dog’s) as Teena’s fur is shampooed.

Mylyn Nguyen’s work highlights the vulnerability we can feel when our personal scent is perceptible to those around us. Growing up in a Vietnamese household in the suburbs of Adelaide, Nguyen associated the medicinal scent of Tiger Balm used by her family to being what she describes as “ethically different”. For Nguyen, particular fragrances marked her as separate from her peers causing feelings of worry and self-consciousness. After reflecting on these feelings of insecurity as an adult, the scent of Tiger Balm is now positively linked to her familial identity and memories of home.

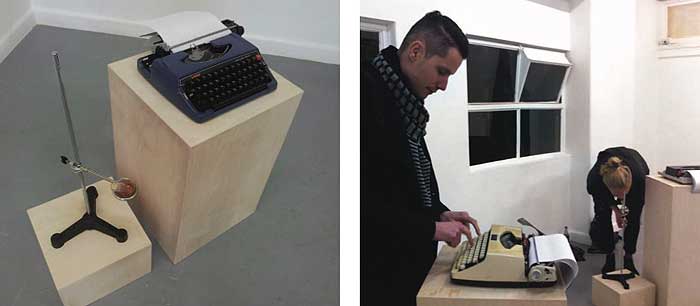

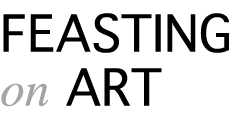

Liz Henderson’s practice studies the link between language and scent. Her installation Untitled (2013) pairs unidentifiable fragrances with typewriters inviting the audience to describe what they smell. The work highlights the difficulty in articulating this specific modality as similes and metaphors are used to express the scents.

Right: Mylyn Nguyen, Monkey Ba (2018_, Merino & acrylic fibre, resin, Tiger Balm, 17 x 32 x 18 cm

Often our senses work in coordination; the flavour of a foodstuff is the combination of taste and smell (and the reason why a blocked nose often dulls the flavour of a meal). A number of artists explore the potential for scent to engender an intersensory encounter whereby the senses overlap and are collectively engaged. In Collected Gathering (2018), Melinda Le Guay condenses the olfactory sensations of her annual Christmas cake into a sculptural form. Comparably, Janet Tavener manipulates sensory perception through her sugar installations. By scenting each object with incongruous fragrances (T-bone steak scented with lemon) she emphasises the accuracy of the bodily senses in perception.

Right: Jo Burzynska, La Chevelure (2016), sound loop – 10:46mins, scent

Jayne McSwiney, Jo Burzynska, and Todd Fuller’s artworks emphasise the potential for crossmodal perception in multisensory encounters. McSwiney applies a synaesthetic interpretation to John Williamson’s song True Blue (1986), correlating a scent to each musical note of the song. Her perfume synthesises the score into a distinct fragrance. Burzynska’s La Chevelure (2016) integrates sound and scent to create an immersive experiential journey devoid of optical referents. Fuller’s Ode to Troughman (2018) is a contemporary adaptation of the 1960s invention of smell-o-vision. His hand-drawn film set in the men’s toilet depicts sexual encounters inspired by legendary 1980s gay figure Troughman. Fuller’s film transports the viewer to the site of the narrative through the distinctive scent of urinal cakes.

Right: Archie Moore, Dis infected (2018), military blanket, Dettol, 155 x 180 cm

Not all scent-induced memories are pleasurable; for many the antiseptic scent of Dettol recalls a hospital or infirmary visit caused by injury or sickness. Archie Moore’s Dis infected (2018), a Dettol soaked military blanket, draws these associations. His artwork references a shared history of pain and sickness, the spread of smallpox and other diseases through blankets distributed to Indigenous communities.

In contrast to our increasingly digitised, screen-based world where the emphasis is on visual communication, this exhibition demands the presence of the viewer as an active participant. The ephemeral encounters privilege the sense of smell over that of vision and emphasise memory as understood through bodily engagement.

(1) Georg Simmel, “Sociology of the Senses,” in Simmel on Culture, eds. David Frisby and Mike Featherstone (London: SAGE Publications, 1997), 119.

———-

Megan Fizell is a PhD candidate at University of New South Wales. reminiSCENT is part of her ongoing exhibition series considering the intersection between food and art with a focus on sensory interaction. Her current research is centred on aesthetic encounters that privilege being or presence over representation and sensory/embodied experience over symbolic convention.

reminiSCENT is on view at MAY SPACE, Sydney from 25 July to 11 August 2018. Read all posts related to the exhibition here, follow along on social media with the hashtag #reminiSCENT2018.

1 comment

Julie says:

Aug 26, 2018

I wish I could have attended this show.